|

"I always hated doing them, and I was glad to give it up." New Zealand is unique in the world for adopting infant circumcision almost universally, and then abandoning it. (A presentation to the Sixth International Symposium on Genital Integrity, Sydney, December 8, 2000, by H. Y. and Ken McGrath.)

New Zealand - or Aotearoa - lies 2000 kilometres east-southeast of Australia.  Its first human inhabitants, arriving more than 650 years ago, were Polynesians from the north-east, from Tahiti or the Cook Islands. At least one of those ancestors was reportedly superincised, because it's in his name, which is in turn embedded in our famous long placename.

The key phrase being ure (penis) haea (lacerated). That he was blown hither from afar, implies he was not incised in New Zealand. That it was worth mentioning suggests it was already rare, and indeed to have an exposed glans was a mark of shame among pre-European Maori.

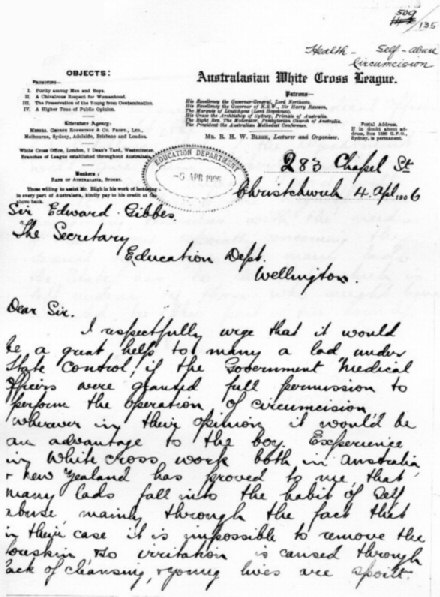

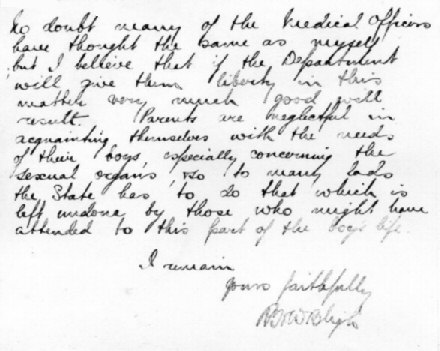

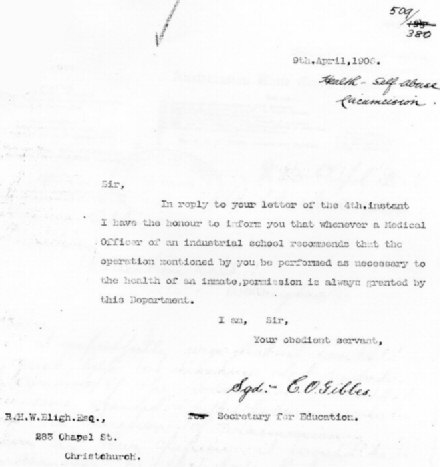

The slitting, when it was done, was by a tohunga or medicine-man, who risked the death penalty if the operation went wrong - something our USAmerican friends might want to copy. Medical circumcision did catch on this century among the Mäori in one tribal region, Waikato. (This may explain why all the modern carvings in the Waikato Art Museum surrounding the bow of the canoe Te Winika portray ancestral figures as circumcised.) Maori meeting houses are lined with rows of large wooden carvings of ancestors, elaborately stylized. Those that show the ancestors' penises - those that escaped the missionaries' chisels - show them as tehe. This is probably not because they were circumcised, but because they have erections, and that is the more tapu (sacred) condition, appropriate to ancestors. European settlers began arriving about 200 years ago, and outnumbered the Maori by some time in the second half of the 19th century. Very few of those Pakeha (white) immigrants would have been circumcised. One doctor who began circumcising in 1916 says it was very rare before the First World War. In 1906, a morals campaigner, R H W Bligh, wrote to the Secretary of Education urging circumcision for boys in state care who masturbated. It was already standard practice.

Two years later, T. Archey, Superintendent of the Burnham Industrial School (a place the young John A. Lee spent years on the run from, and described as "hell") asked the Secretary for Education for "a small Government Hospital" to be erected in Christchurch for all State Children in the Canterbury district, especially for the "number of boys here who would undoubtedly be benefitted by being circumcised." For example, "this operation would remove the irritation that causes ---- --. --------- to act as he has in the past." He was told that this was out of the question, but that "the operation that you refer to might be done at the school, say two at a time." In reply, Archey said two "qualified medical men" would be required, one to administer chloroform, but this could be done on an outpatient basis at Christchurch Hospital, and the Secretary for Education told him to proceed on that basis.

There are some hints that fear of venereal disease - for which only limited treatments were available - during and after the First World War gave circumcision its next toehold. We have searched in vain for official information or statistics about its rise in New Zealand - this is doubly remarkable after 1938 when the first Labour Government's new "cradle-to-grave" Social Security system began paying for it. In 1926, a doctor at St Helens Hospital, Auckland, asked the Health Department to be reimbursed for anaesthetic for circumcisions there. In the course of the Deparment's inquries, the Director-General, Dr T H A Valentine, referred to his increasing concern about the operations. He was reassured to learn that the doctor had perforemed only two circumcisions in three months, saying the doctor "doesn't seem to be overdoing things." and the Medical Officer of Health, Dr Watt, commented that "two only in 3 months is extremely moderate". They seem to have been concerned at the rise in non-therapeutic circumcision. Until 1967, doctors in New Zealand all belonged to the New Zealand Branch of the British Medical Association, and most did any postgraduate study in England. To a first approximation, we hypothesise that the rise of circumcision in New Zealand was doctor-driven, and closely paralleled its rise in Britain. Carne has a figure of 34.4% circumcised, of a sample of 14 hundred boys born in Britain in 1930 to 1936. (graph point 1) We are lucky that from 1961 to 1976, fifth-year medical students were routinely set circumcision as a dissertation topic. One surveyed 41 doctors born between 1914 and 1934 and found three out of five were themselves circumcised, nearly twice the British average, perhaps reflecting their class or class-aspirations, (and perhaps affecting their view of the practice). (graph point 2) New Zealand has long prided itself on being a classless society. That's less than the truth, the great majority correspond to the British middle class - but few could not afford circumcision. However, it was a highly conformist society, and a doctors' word was all but law. Through the 20th century, the care of babies in New Zealand gradually fell into, and then out of, the hands of a unique institution, the Plunket Society. The Society for Promoting the Health of Women and Children, nicknamed after its first patron, was founded by Dr Frederic Truby King (later Sir Truby, 1858-1938) in 1907 to teach babycare and promote maternal and infant heath. His teachings became widespread throughout the British Empire. Much of his teaching was benign and life-saving. More recently it has been criticised as authoritarian and rigid. Truby King himself was not in favour of routine circumcision -

- but he advocated premature retraction -

It may well be that this policy itself generated sufficient foreskin problems to make childhood circumcision commonplace, and give truth to the common assertion that "He'll only have to have it done later." By 1930, 65 percent of all non-Maori infants were under the control and care of Plunket, by 1947, 85 percent. The Society largely ignored Maori children. New Zealand's foremost poet, James K. Baxter, born in 1926, wrote:

He was born in a nursing home, so it would have been only his poetic licence that the nurse actually did it (like the claim in the last line). The nurse would not have used scissors, in any case. The great majority of circumcisions in New Zealand were performed freehand,  a pair of bone-forceps being used to isolate the glans, provide a straight cut, crush the foreskin, and give haemostasis while a scalpel did the cutting. Dr George McCall Smith, a remarkable man, a sort of A S Neill or John Dewey of medicine, declared his Hokianga Special Medical Area a circumcision-free zone.  He directly accused the Plunket Nurses themselves of circumcising:

- but this appears to be poetic licence. During and after World War Two, a very common reason for circumcising was "He might have to fight in the desert. He could get an infection under his foreskin and have to be circumcised then. Better to do it now." This claim, "the sand myth," is rebutted in detail on another page. It was responsible for a large but unknown number of circumcisions. What may have given rise to this is that, in 1940, in order to lower the incidence of men rejected for service, it was decided that the army would pay for minor remedial treatments in civilian hospitals. Only disabilities that could be corrected and would allow the recruit to enter camp within one month after his operation were initially considered. Arrangements were made for such treatments to be carried out at public hospitals, in-patient treatment usually being required. Types suitable for remedial treatment were: enlarged tonsils; circumcision; minor toe operations (hammer toe and overlapping toe); undescended testicle; varicocele of severe degree; hydrocele; and minor degree of varicose veins (not above the knee), where only one, or at the most two, treatments were required for cure. - Stout, T. Duncan M., Medical Services in New Zealand and The Pacific, The doctors interviewed in the 1960s often mentioned wartime hygiene problems with troops, and one noted that circumcision peaked in popularity after each World War.

There is ample anecdotal evidence that circumcision was much more prevalent after the war than in Britain. Psychiatrist Maurice Bevan-Brown - mainly concerned about the emotional effects on the child - wrote in 1948:

(The cartoon is by a patient who, with neo-Freudian Bevan-Brown's help, found the ogress to represent his mother, and the knife to be just a symbol for a bottle of milk - but sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, and sometimes a knife is just a knife.) In 1949, Douglas Gairdner had his landmark paper, The Fate of the Foreskin, published in the BMJ, which all New Zealand doctors would receive. Lacking any other reason, we conclude, this triggered the decline. They would not have known that Britain's National Health Service had stopped paying for it two years earlier.

Once a significant number of men were circumcised, circumcision for conformity's sake came into play in our very conformist society, and in 1977, when Shannon, Horwood and Fergusson found the rate of circumcision in Christchurch had fallen to 24 per cent (graph point 5), a circumcised father was the biggest single risk factor. That same longitudinal study of 590 boys, the city's entire birth cohort for three and a half months, also found that by the mothers' report, 62 percent of fathers (and 34 per cent of elder brothers) were circumcised. This gives us a rough estimate for men born about 1934-44 (graph point 3). The fathers and brothers may not have been born in New Zealand, however.) But our own contemporaries, born 1941 to 1948, were approximately 95% circumcised (graph point 4), and reports of intact boys being stigmatised date back as far as the birth-year of 1940 - before the sand-myth could have had effect. Crothers studied a smaller cohort in Wellington during the same period (1977) with a similar result to Shannon et al. She also found that only seven percent of mothers said their doctors had recommended circumcision. Seven years earlier a public health official had asked for some more consistent policy:

We don't know where he gets the figure of 70% (graph point 8) from, but his view is clear if not original - the term "chronic remunerative surgery" was used by W.K.C. Morgan in his article "Penile plunder" (Med J Aust 1967;1:1102-03). Silva found 36.6% of 527 boys born in Dunedin in 1972-3 were circumcised (graph point 9). So it seems the tide went out some time after the war, driven out as it had been driven in, by doctors, but delayed by considerable parental pressure. And grandparental: Some time around 1980, a colleague of the author took her daughter to six different doctors before they could find one to circumcise her grandson. Shannon et al had found grandmother's opinion to be the next greatest risk factor after father's circumcision. In 1972 some mothers still thought it was done as a matter of course. One possible turning point is that when National Women's Hospital opened in Auckland in 1962 (graph "NWH"), the order came down from the Professorial Board, personified by Professor Denis Bonham, that circumcision was not to be done there at public expense. Private doctors would be given a tray and a small operating theatre and left to it if they wished. By 1976 it was nearly universal not to raise the subject - a "sleeping dogs" policy. In 1986, no circumcision instruments could be found at National Women's. In the Waikato district in 1989 the circumcision rate had fallen to 7 per cent. (graph point 6) Official hospital circumcision statistics are available for the period 1980-1995, but they are incomplete and ambiguous. While circumcisions in public hospitals fell to residual levels, many boys seem to have been simply taken to private hospitals instead. Late-breaking news: we do have a final data point for circumcisions in public hospitals in 1995 - 0.35% (applause). (graph point 7) But also, some hundreds of boys a year were being treated in public hospitals for "redundant prepuce and phimosis" - a catchall diagnosis for two contradictory penile configurations. When we have both figures, rp&p and circumcision, they correspond quite well, so we may suspect these led to unrecorded circumcisions. Still others would have been done in doctors' surgeries. Thus among Pakeha, we can plot the decline, if not the rise, of circumcision. Throughout this decline, there was virtually no discussion of circumcision in the public media. The 1950s and early 60s were a time of strong social conformity and sexual taboo. New Zealand identified itself as European or British, so unlike in the US, circumcision was never associated with national identity. In the 1960s, a growing influx of Pacific Islanders, especially Samoans and Tongans, began to settle, especially to South Auckland. The missionaries had already replaced their custom of child superincision with infant circumcision. It remains heavily entrenched, being regarded as essential for full manhood, especially the right to speak in public. Two publicly funded clinics in South Auckland continue to perform the operation, sometimes on unwilling boys. Male relatives form so-called "raiding parties" to take the boys to clinics. To forestall that, Polynesian boys are usually circumcised in infancy. One Polynesian doctor in Auckland is trying to bring back the traditional custom of the dorsal slit, or superincision. Another, in Christchurch will do it, but under general anaesthetic at six months.

New Zealand had 6,636 Jews at the 2001 census, 162 of them males aged 0-4, suggesting ~32 circumcisions/year, and when the occasion arises, a doctor-mohel is flown in from Sydney every six months or so, to circumcise in batches - breaking the covenantal requirment that it be done on the eighth day. In 2001 there were 23,631 Muslims, 3591 males under 15, suggesting ~240 circumcisions/year. One doctor in Wellington will circumcise on request, but in many cities, none will. So we see that it was never customary among the Maori, and always customary among other Pacific Islanders, but among Pakeha, or white New Zealanders, it arose in silence and declined in silence. As two doctors separately said to each of us, in more or less the same words, "I always hated doing them, and I was glad to give it up." In New Zealand, a speech without a song is like a penis without a foreskin, incomplete and increasingly rare, but I have my marching orders, so just, thrice greetings to you all - Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa.

As one New Zealander put it in a television documentary: "I'm just real glad I've got a foreskin, eh. It's a primo little thing."

Commissioner for Children doubts legality

- "Foreskin's Lament"

And finally, for New Zealanders...  Related pages:

Back to the Intactivism index page.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||