"Not for you" - Mantegna's "Circumcision"Andrea Mantegna's painting of Christ's Circumcision makes some interesting points about its (lack of a) role in Christianity. Also Mazzolino's, Tura's and Goltzius' pictures of the same scene.

c. 1470, 86x42.5cm, Florence, Uffizi In the top left lunette, we see a dramatic Old Testament scene, Abraham at the moment (Gen. 22 10) when he is about to kill Isaac:

It is not the moment when he is about to circumcise himself, (Gen. 13 24) nor his 13 year old son Ishmael (Gen. 17 25), which might be considered more direct precedents. The circumcision of Jesus, as discussed elsewhere, was not required to purify him of original sin, but was done because of his obedience to the Law when, as the Father, he chose to be incarnated as a human, a male and a Jew. The Church Fathers do not seem to have noticed that as the Father, he himself had made the Law, any more than the artist noticed how unlikely it was for these "graven Images" to decorate a temple or synagogue. In the top right lunette, a man holds up a tablet.

He can be identified as Moses by his horns (which Michaelangelo also illustrated in his statue in the church of St Peter in Chains, Rome), though they result from a mistranslation of Exod. 34 29 and 35, "his face shone" (karan) as "his face had horns" (kæren - English spellings vary). Again this emphasises the Laws God is said to have given him, though circumcision is not among the Ten Commandments but the 613 mitzvot now all observed only by the strictest of Orthodox Jews. At the bottom right, a woman turns a child's head from the central scene, as if to say, as Steinberg observes, "Not for you":

(In strict literalness, the child would have been circumcised long since, but it was a Renaissance commonplace to introduce present-day observers, such as the families of patrons, into Biblical scenes.) The boy holds a broken ring near his own penis, which I suggest the artist intended to represent the end of the old covenant of circumcision. At the centre of the scene, the child Jesus himself turns piteously away from the old man with the knife, towards the one person who might be expected to protect him, his Mother.

Since the circumcision of Jesus was seen as prefiguring his final wounds, I see a deliberate parallel being made here with the agony in the Garden of Gethsemene , when Jesus is reported to have said, "O My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as You will." (Matt 26 39) There is no doubt in the painter's mind that circumcision (like crucifixion) is extremely painful. According to Lev. 12 4, the mother ought not even to be there, since she is still "unclean", but presumably Christian theology overrules Jewish here, and the Virgin is anything but "unclean". The illustration of the mohel is curious.

UnJewishly, his head is uncovered. Perhaps his halo is deemed sufficient covering, or a substitute, but if he is a saint, he has no name. He strongly resembles one of the Magi in the Adoration of the Magi (the central scene of the tryptich of which the "Circumcision" is now the first), who also casts a beady, but not so purposeful, eye on Christ's genitalia. His instruments, like the costumes and building, are of the 15th century.

It is doubtful that anything is meaningless in this picture, and it is not too fantastic to suppose that the ewer or jug on the ledge nearby stands for baptism, as the Christian replacement for circumcision.

The man on the left, presumably Joseph, might be grasping his own penis in sympathy with the baby.

With his other hand, he holds two birds in a basket.

This is a reference to the offerings made after the birth of a child, according to Lev. 12 8, though they ought normally to wait 33 more days, until the child's mother has been "purified", and according to Luke 2 21-2, they did. One is a burnt offering, the other a sin-offering - though again, in Christian thought, Jesus was born without sin. Significantly, two turtle-doves or young pigeons may be sacrificed only if the mother is not able to bring a lamb. Doubtless one Lamb is deemed to be there for the sacrifice already. In some collections the name of the painting is bowdlerised to

"The Presentation in theTemple". Mazzolino's "Circumcision" "Circumcision" by Ludovico Mazzolino (1480 – c. 1528) painted 1525  - again shows Jesus turning away

from what is being done to him.

-and a man twisting his leg

to keep a child from seeing what is being done to the baby.

His water jug may again foreshadow baptism to replace genital

cutting.

- Ufizzi gallery, Florence

photo by Matthew Weyer Another "Circumcision" by Mazzolino

(c.1520)

shows Mary with swollen eyes,

presumably from weeping.

- Collezione Vittorio Cini,

Venice

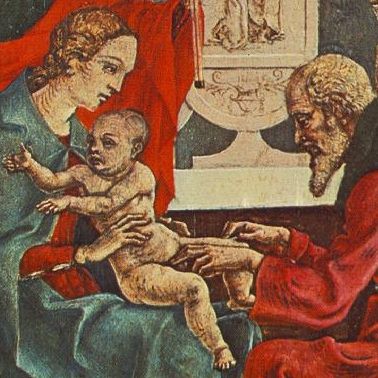

Tura's 'Circumcision' The Circumcision (from the predella of the Roverella Polyptych, 1474) by Cosme Tura is somewhat similar, but less interesting:

Tempera on wood, diameter 38 cm Like Mantegna's, the child turns away from what is being done

to him, but also from his mother, whose attention is elsewhere.

It is not nearly as clear here what is being done, and anyone

who didn't know what was happening would think the old man was

stroking the boy's genitals. As with many Renaissance

nativities, and more so than the Mantegna, Jesus appears

outlandishly old

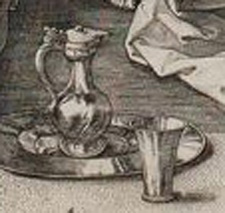

Goltzius' 'Circumcision' Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558-1617) sets his "Circumcision" in a sequence of the "Life of the Virgin" (1594):  Engraving on paper 480 x 354 mm He places it in a side-chapel of a large contemporary (Dutch) church, albeit with no Christian imagery, the men with heads uncovered. The mohel has the same intent look as in Mantegna's work. He appears to be pulling Jesus' foreskin with his left finger and thumb as he cuts with his right hand. The baby seems to be sharing a gaze with his father and reaching out for help, in vain:

Again there is a ewer and tumbler (with detailed reflections), now in the foreground.  |