| |

Circumcision and HIV - the Randomised

Controlled Trials

'Circumcision Vindicated At Last!' ? - hardly

|

The American mind seems extremely vulnerable to the

belief that any alleged knowledge which can be

expressed in figures is in fact as final and exact as

the figures in which it is expressed.

- Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism

in

American Life,

quoted by Charles Seife in Proofiness

|

After centuries of circumcision searching for a disease to

cure, and the emergence of a new one that is sexually

transmitted, it may be that a link has actually, finally

been found. This still falls very far short of justifying

Routine Infant Circumcision, however, despite the headline of a

Toronto columnist trumpetting "Circumcision Vindicated At Last!"

The latest

studies are the most careful so far to avoid the

mistakes of their predecessors:

|

National

Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

12:00 Noon ET

Adult Male Circumcision

Significantly Reduces Risk of Acquiring HIV

[A surgical miracle! No hint

of the many caveats to follow.]

Trials in Kenya and Uganda Stopped Early

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious

Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of

Health (NIH), announced an early end to two clinical

trials of adult male circumcision because an interim

review of trial data revealed that medically performed

circumcision significantly reduces a man's risk of

acquiring HIV through heterosexual intercourse. The

trial in Kisumu, Kenya, of 2,784 HIV-negative men

showed a 53 percent reduction of HIV acquisition in

circumcised men relative to uncircumcised men, while a

trial of 4,996 HIV-negative men in Rakai, Uganda,

showed that HIV acquisition was reduced by 48 percent

in circumcised men. ["Impressive

sounding reductions in relative risk can mask much

smaller reductions in absolute risk." - editorial

in

the British Medical Journal, January 19,

2008. In fact they are inevitably greater, but

their actual utility depends on the absolute risk.]

"These findings are of great interest to public

health policy makers who are developing and

implementing comprehensive HIV prevention

programs,"says NIH Director Elias A. Zerhouni, M.D.

"Male circumcision performed safely in a medical

environment complements other HIV prevention

strategies and could lessen the burden of HIV/AIDS,

especially in countries in sub-Saharan Africa where,

according to the 2006 estimates from UNAIDS, 2.8

million new infections occurred in a single year."

"Many studies have suggested that male circumcision

plays a role in protecting against HIV acquisition,"

notes NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D. "We now

have confirmation — from large, carefully controlled,

randomized clinical trials [the

randomisation was only in the assignment of the

paid volunteers to experimental or control groups;

they were not a random sample of the population.

The trials were not - by the nature of

circumcision, could not be - double blinded or

placebo controlled, the gold standard of clinical

trials.] — showing definitively that

medically performed circumcision can significantly

lower the risk of adult males contracting HIV through

heterosexual intercourse. While the initial benefit

will be fewer HIV infections in men, ultimately adult

male circumcision could lead to fewer infections in

women in those areas of the world where HIV is spread

primarily through heterosexual intercourse."

The findings from the African studies may have less

impact on the epidemic in the United States for

several reasons. In the United States, most men have

been circumcised. Also, there is a lower prevalence of

HIV. Moreover, most infections among men in the United

States are in men who have sex with men, for whom the

amount of benefit [if any]

provided by circumcision is unknown [but

is

likely to be much less, because HIV is known to be

more readily transmitted to the receptive male

partner]. Nonetheless, the overall

findings of the African studies are likely to be

broadly relevant regardless of geographic location: a

man at sexual risk who is uncircumcised is more likely

than a man who is circumcised to become infected with

HIV. Still, circumcision is only part of a broader HIV

prevention strategy that includes limiting the number

of sexual partners and using condoms during

intercourse. [In that case,

any benefit provided by circumcision would only

apply in the rare cases where a condom breaks or

comes off.]

The co-principal investigators of the Kenyan trial

are Robert Bailey, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of

Illinois at Chicago, and Stephen Moses, M.D., M.P.H.,

University of Manitoba, Canada. In addition to NIAID

support, the Kenyan trial was funded by the Canadian

Institutes of Health Research and included Kenyan

researchers Jeckoniah Ndinya-Achola, M.B.Ch.B., and

Kawango Agot, Ph.D., M.P.H. The Ugandan trial is led

by Ronald Gray, M.B.B.S., M.Sc., of Johns Hopkins

Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore,

Maryland. Additional collaborators in the Ugandan

trial were David Serwadda, M.Med., M.Sc., M.P.H.,

Nelson Sewankambo, M.B.Ch.B., M.Med.M.Sc., Stephen

Watya, M.B.Ch.B., M.Med., and Godfrey Kigozi,

M.B.Ch.B., M.P.H.

Both trials involved adult, HIV-negative heterosexual

male volunteers assigned at random to either

intervention (circumcision performed by trained

medical professionals in a clinic setting) or no

intervention (no circumcision). All participants were

extensively counseled in HIV prevention and risk

reduction techniques.

[With AIDS running at 4.10%

in the population (according the the CIA's

World

Factbook), selecting men who are

HIV-negative means that already

- they are likely to have

some natural immunity

- they are likely to be

more careful than the average person and

the fact that they volunteer

implies they have more concern about HIV/AIDS than

others. These introduces biases that make

circumcision likely to be less effective when

applied to the general population.]

Both trials reached their enrollment targets by

September 2005 and were originally designed to

continue follow-up until mid-2007. However, at the

regularly scheduled meeting of the NIAID Data and

Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) on December 12, 2006,

reviewers assessed the interim data and deemed

medically performed circumcision safe and effective in

reducing HIV acquisition in both trials. They

therefore recommended the two studies be halted early.

All men who were randomized into the non-intervention

arms will now be offered circumcision.

[For statistical reasons,

effectiveness of a treatment declines with the

passage of time. Cutting the experiment short

gives a falsely optimistic outcome.]

"It is critical to emphasize that these clinical

trials demonstrated that medical circumcision is safe

and effective when the procedure is performed by

medically trained professionals and when patients

receive appropriate care during the healing period

following surgery," notes Dr. Fauci.

[But once the meme

"Circumcision prevents HIV" is loose in the

community, this will be forgotten and

circumcisions will be done under unhygienic

conditions with shared instruments, quite possibly

under duress.]

Researchers have noted significant variations in HIV

prevalence that seemed, at least in certain African

and Asian countries, to be associated with levels of

male circumcision in the community. In areas where

circumcision is common, HIV prevalence tends to be

lower; conversely, areas of higher HIV prevalence

overlapped with regions where male circumcision is not

commonly practiced.

[These correlations require

highly selective use of statistics. There are many

exceptions: HIV is rare in Cuba, where

circumcision is also rare, and common in Lesotho,

where circumcision is common, and common among

both the Zulu of South Africa who do not

circumcise, and the Xhosa, who do.]

Results of the first randomized clinical trial

assessing the protective value of male circumcision

against HIV infection, conducted by a team of French

and South African researchers in South Africa, were

reported in 2005. That trial of more than 3,000

HIV-negative men showed that circumcision reduced the

risk of acquiring HIV by 60 percent. The trial was

funded by the French Agence Nationale de Recherches

sur le Sida (ANRS) (see http://www.anrs.fr/).

[Earlier studies claimed an

eight-fold reduction. As each new study corrects

the errors of its predecessors, the claimed

benefit goes down. In this, it resembles

parapsychological research. The suspicion arises

that when all confounding factors have been

allowed for, circumcision will confer no benefit

at all.

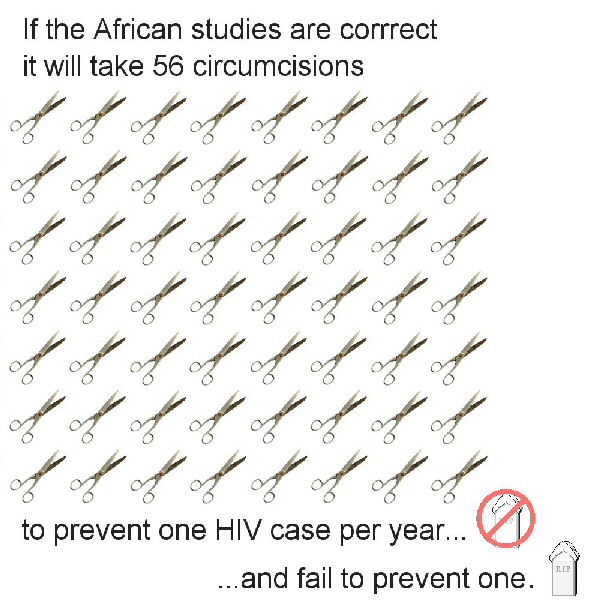

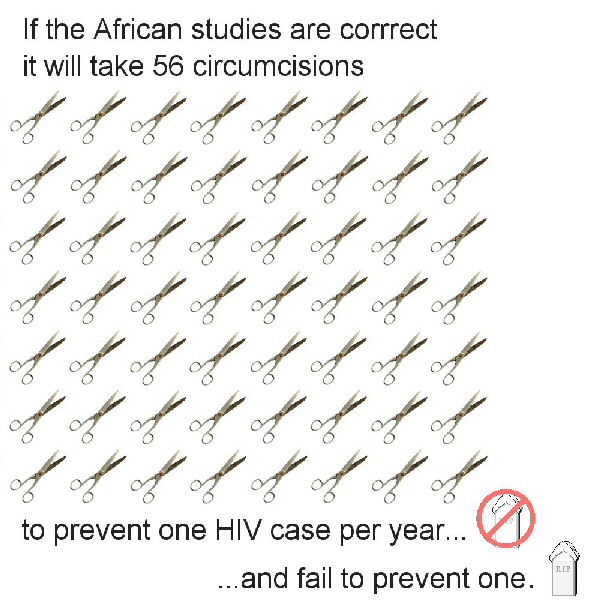

The Relative Risk Reduction

of 53% seems impressive, but when the rates of HIV

infection in the experimental and control

populations are considered, the results are less

impressive.

|

Cut infection rate in

12 months

|

1.58%

|

|

Intact infect. rate

in 12 months

|

3.38%

|

|

Absolute risk

reduction

|

1.8 (95% CI:

0.64-2.95)

|

|

Relative risk

reduction

|

53% (95% CI: 23-72)

|

|

Odds ratio

|

0.45 (95% CI:

0.27-0.77)

|

|

Number needed to

treat in 1 year

|

56 (95% CI:

34-155)

|

|

In other words, you

would have to circumcise 56 men to

prevent one of them contracting HIV in

one year.

Click

on the image for an enlarged version

Click

on the image for an enlarged version

And the number needed

to prevent HIV longer term is higher.

Doctors could spend their time better

spent treating people with ulcerative

disease and malaria, which make HIV

transmission easier

and using the money saved to promote safer

sexual practices.

Few accepted medicines have such a high

NNT.

On this basis, the NNT in developed

countries such as the USA, where the HIV

rate is relatively low (0.6% compared to

4.1% in Uganda), would be much higher - it

would take 380 circumcisions in

the US to prevent one case of HIV.

|

For more information on the Kenyan and Ugandan trials

of adult male circumcision, see the NIAID Questions

and Answers document at http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/news/QA/AMC12_QA.htm.

|

...

4. What is adult male circumcision and

how was it performed in these studies?

... The circumcision procedure used in the

Kenyan trial was the foreskin clamp method.

... [This is

substantially the same as the tribal

method, blamed in Lesotho, where AIDS is

rife, for not taking enough mucosa]

The Kenyan trial procedure took about 25

minutes and used stitches to control

bleeding and improve wound closure. The

circumcision procedure used in the Ugandan

trial is known as the sleeve method and

takes about 30 minutes. [This

can take a variable amount of mucosa

depending where the "sleeve" is taken

from] The Ugandan trial used

cauterization of the blood vessels to

control bleeding and stitches to close the

wound. Both methods are commonly used

throughout the world.

.... Both trials recruited healthy,

HIV-negative uncircumcised men who planned

to remain near the study site for the

duration of the trial.

[This selects for

any natural immunity, and weeds out

itinerants, such as truck-drivers, who

are at higher risk of HIV, because of

their greater variety of partners.]

...men in the trials were cautioned to not

resume sexual activity until the incision

was fully healed and checked by the

physician....

|

From the Manual

of

Male Circumcision (October

2006), p 62

Avoid any sport, strenuous

activity, masturbation or sexual

intercourse for four to six weeks.

The healing process is well

advanced by 7 days but it takes 3

to 4 weeks for the wound to become

fully strong. Sexual intercourse

can be started after 4 to 6 weeks,

but it is best to use a condom as

this helps protect the newly

healed wound. It is always wise to

use a condom if there is any risk

of HIV infection. This is

particularly important after

circumcision as the newly healed

wound may be a weak point for two

or three months.

|

[As with the

Orange Farm study, this makes a

significant difference between the

experimental (cut) and control (intact)

group. The control group could have been

given a placebo operation, or another

kind of placebo, and the same

instructions. Even then, since the test

can not be made double blind (neither

experimenters nor subjects knowing who

is circumcised), errors will occur.]

...As with most prevention strategies,

adult male circumcision is not completely

effective at preventing HIV transmission. Millions of circumcised

men have become infected with HIV

through heterosexual exposure to the

virus. Men who receive adult

male circumcision may perceive that they are

at decreased risk for transmission and,

therefore, may not maintain other risk

reduction strategies. Modest increases in

the number of sexual partners could negate

the protective effect and increase the rate

of HIV transmission in a community. Adult

male circumcision will be most effective

when integrated into a comprehensive

prevention strategy which includes the ABCs

(Abstinence, Be Faithful, and Condoms) of

HIV prevention.

[This is the Nail Soup method

of using circumcision to prevent HIV.]

The World Health Organization (WHO) press

statement in response to the NIAID DSMB

recommendation is available on the WHO web

site, www.who.int/hiv.

|

And from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2006/np18/en/

WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF

and the UNAIDS Secretariat

emphasize that their current

policy position has not

changed and that they do not

currently recommend the

promotion of male circumcision

for HIV prevention purposes.

However, the UN recognizes the

importance of anticipating and

preparing for possible

increased demand for

circumcision if the current

trials confirm the protective

effect of the practice.

|

To a summary

critique of HIV claims.

|

|

An earlier

study:

|

Abstract

Impact of male circumcision on the female-to-male

transmission of HIV Auvert B.1, Puren A.2,

Taljaard D.3, Lagarde E.4, Sitta

R.4, Tambekou J.4

1 UVSQ - INSERM U687 - APHP, ST

Maurice CEDEX, France, 2 NICD, Johannesburg, South

Africa, 3 Progressus CC, Johannesburg, South Africa,

4 INSERM U687, St Maurice, France

Introduction: Observational studies suggest

that male circumcision could protect against HIV-1

acquisition. A randomized control intervention trial

to test this hypothesis was performed in sub-Saharan

Africa with a high prevalence of HIV and where the

mode of transmission is through sexual contact.

Methods: 3273 uncircumcised men, aged 18-24

and wishing to be circumcised,

were randomized in a control and intervention group.

Men were followed for 21 months with an inclusion

visit and follow-up visits at month 3, 12 and 21. Male

circumcision was offered to the intervention group

just after randomization and to the control group at

the end of 21 month follow-up visit. Male

circumcisions were performed by medical doctors. At

each visit, sexual behavior was assessed by a

questionnaire and a blood sample was taken for HIV

serology. These grouped censored data were analyzed in

an “intention to prevent” univariate and multivariate

analysis using the piecewise survival model, and

relative risk (RR) of HIV infection with 95%

confidence interval (95% CI) was determined.

Results: Loss to follow-up was <11%; <1%

of the intervention group were not circumcised and

< 2% of the control group were circumcised during

the follow-up. We observed 45 HIV infections in the

control group and 15 in the intervention group,

RR=2.77 (95% CI: 1.56 – 4.91; p=0.0005). When

controlling for sexual behavior, including condom use

and health seeking behavior, the RR was unchanged:

RR=2.93 (p=0.0003).

Conclusions: Male circumcision provides a high

degree of protection against HIV infection

acquisition. Male circumcision is equivalent

to

a vaccine with a 63% efficacy. The promotion of

male circumcision in uncircumcised males will reduce

HIV incidence among men and indirectly will protect

females and children from HIV infection. Male

circumcision must be recognized as an important means

to fight the spread of HIV infection and the

international community must mobilize to promote it.

|

|

Some

factors casting doubt on the findings:

-

A summary

of the study includes this:

|

Inclusion criteria:

...

Consenting to avoid sexual contact

(except with condom protection) during

the 6 weeks following the medicalized

circumcision

|

The

experimental (circumcised) men, but not the

control group (left intact), were

told:

|

When you are circumcised you will be

asked to have no sexual contact in the 6

weeks after surgery. To have sexual

contact before your skin of your penis

is completely healed, could lead to

infection if your partner is infected

with a sexually transmitted disease. It

could also be painful and lead to

bleeding. If you desire to have sexual

contact in the 6 weeks after surgery,

despite our recommendation, it is

absolutely essential that your (sic)

use a condom.

|

So:

1.

The circumcised experimental group, but not the

intact control group, got into the HABIT of

using condoms

2. They learnt HOW to use condoms

3. They had to make sure they HAD condoms (which

are in scandalously short supply in South

Africa), and

4. last but not least, they were PROTECTED by

condoms.

The

researchers could hardly say to the experimental

group, "but after that you don't have to use

condoms" could they?

Meanwhile

the intact control group was not required to use

condoms for the first six weeks of the study,

just sent out to take their chances.

This

throws the results into, er, a cocked hat.

- The

circumcised men would have had to take some time

away from any sexual activity, reducing their

exposure to HIV.

- The

circumcised men would inevitably get more exposure

to safe-sex information during their time in

medical hands, waiting for and recovering from,

their operations.

- Humans

are not lab rats. They have sex in non-random

ways. Many of the men in the study would put

themselves at little or no risk of contracting

HIV, a few at great risk, so the effective sample

size is much smaller than it appears, making the

margin of error much larger.

- Because

HIV-positive men were excluded from the study,

there would have been a higher proportion of men

with natural immunity in both groups than the

general population, reducing the effective sample

size still further.

- Because

all the subjects did not just agree to be

circumcised but wished to be, they were

not a representative sample of the general

population.

- 11-14

percent of the original participants (360 - 458

men) were lost to study or disqualified from

continuing. Their HIV status and/or circumcision

status might not be typical of the total (for

example, if they dropped out because they lost

interest in the experiment when they found

circumcision had not protected them), introducing

sufficient bias to refute the claimed finding.

- Michel

Garenne of the Institut Pasteur in Paris points

out that the

claimed

63% efficacy is not comparable to that of a

vaccine and would result in considerable

infection over time.

- Jennifer

Vines, MD, of the Oregon Health & Science

University in Portland, comments

"...the authors did not control for other sources

of HIV transimission such as blood transfusions or

exposure through infected needles. ... Controlling

for this route of infection could result in a

smaller difference between HIV infection rates in

the circumcised versus uncircumcised groups,

indicating that circumcision may not be as

effective at decreasing HIV transmission as the

article suggests."

- Columnist

Stephen Strauss (below)

points out that the study was cut short before

even half as many men were infected as were

infected before it began.

- The

Lancet (which earlier published a strident

call for circumcision by Robert Bailey) refused to

publish the study (apparently with ethical

concerns about not telling men they had HIV). The

study has been published by the Public

Library

of Science, an "open source" online medium.

- The

Abstract of the AIDS Conference in Rio reported 15

seroconversions from the circumcised group and 45

seroconversions in the uncircumcised group. (The

New Scientist, 6 August, reported 15

seroconversions in the circumcised group but 51 in

the uncircumcised group. On 29 July the Science

and Development Network reported 18

seroconversions in the circumcised group and 51 in

the uncircumcised group.) On 23 October, PLoS

reported that there were 20 seroconversions in the

circumcised group and 49 in the uncircumcised

group. From the official figures: 15-45 at the

AIDS Conference in Brazil and 20-49 in the PLoS

Journal, between 1 August and 23 October there

appear to have been 4 seroconversions among the

uncircumcised and 5 seroconversions among the

circumcised: in less than 3 months, a 3:1

difference has shrunk to 2.45:1 difference.

- We've

seen it many times before. Circumcision is touted

as the great panacea for this or that dreaded

disease of the age - but as the studies are

refined, the advantage withers away.

- The

rampant evangelism of the Conclusion suggests that

the experimenters are not altogether detached.

Even

if the findings are correct:

- If

they are acted on outside this controlled setting,

men with a keratinised,

reduced penis would be less likely to use condoms.

- The

biggest danger, still unmeasured, is that the

mantra "Circumcision prevents AIDS" will become

widespread, and circumcised men will take no other

precautions, spreading more HIV than their

circumcision prevents. Beliefs like "Sex with a

virgin cures AIDS" are already widespread in

Africa. Circumcision is a painful, memorable

operation that makes a permanent, visible change

to the penis: it would be a resolute man who

didn't feel it had made him safer - and therefore

act less safely.

-

There is some suggestion that circumcision

increases male-to-female

transmission. If so, promoting it could be

disastrous.

- As

UNAIDS said in

2000, relying on circumcision to protect against

AIDS if it offers only this level of protection is

like playing Russian roulette (with one bullet in

the chamber instead of three).

Relying on circumcision to halt the AIDS epidemic

is like fighting a housefire with a soda-syphon.

- While

a vaccine can be improved, this quite limited

preventive effect is as much as circumcision can

ever possibly give.

- Rather

than "Circumcision prevents HIV transmission" it

would put matters in a better perspective to say

"Circumcision (on average) delays HIV

transmission". If the findings of this study are

correct, where an intact man can expect to be

infected with HIV after a year, for a circumcised

man it would take two years more.

- "Protective

effect" over time depends not only on the

reduction in transmission per year, but also the

incidence (baseline rate of transmission).

Where

incidence is high, as it is in Africa,

"protective effect" over time is much less than

the figure for one year would suggest.

- So

rather than say "therefore men should be

circumcised (to make unprotected sex somewhat

safer)", the message should be "intact men should

be especially sure that the sex they have is

protected."

- In

STATS, Rebecca

Goldin points out that the low HIV/AIDS rate in

the US means it would require 10,000 circumcisions

to prevent 5.5 HIV infections, so the risks of

circumcision are at least comparable.

- This

(perhaps) makes a case for voluntary adult

circumcision. Babies still have a right not to be

second-guessed about their sexual practice 16 or

so years from now, the availability of a vaccine

then, or their wishes about what parts of their

body they may keep.

|

|

The misleading Relative Risk Ratio

Newspapers like big numbers and eye-catching

headlines. They need miracle cures and hidden scares,

and small percentage shifts in risk will never be

enough for them to sell readers to advertisers

(because that is the business model). To this end they

pick the single most melodramatic and misleading way

of describing any statistical increase in risk, which

is called the 'relative risk increase'. [Or

"Reduction" in the case of circumcision and HIV]

Let's say the risk of having a heart attack in your

fifties is 50 per cent higher if you have high

cholesterol. That sounds pretty bad. Let's say the

extra risk of having a heart attack if you have high

cholesterol is only 2 per cent. That sounds OK to me.

But they're the same (hypothetical) figures. Let's try

this. Out of a hundred men in their fifties with

normal cholesterol, four will be expected to have a

heart attack; whereas out of a hundred men with high

cholesterol, six will be expected to have a heart

attack. That's two extra heart attacks per hundred.

Those are called 'natural frequencies'.

Natural frequencies are readily understandable,

because instead of using probabilities, or

percentages, or anything even slightly technical or

difficult, they use concrete numbers, just like the

ones you use every day to check if you've lost a kid

on a coach trip, or got the right change in a shop.

Lots of people have argued that we evolved to reason

and do maths with concrete numbers like these, and not

with probabilities, so we find them more intuitive.

Simple numbers are simple.

The other methods of describing the increase have

names too. From our example above, with high

cholesterol, you could have a 50 per cent increase in

risk (the 'relative risk increase'); or a 2 per cent

increase in risk (the 'absolute risk increase'); or,

let me ram it home, the easy one, the informative one,

an extra two heart attacks for every hundred men, the

natural frequency.

As well as being the most comprehensible option,

natural frequencies also contain more information than

the journalists' 'relative risk increase'.

"Bad Science" by Ben Goldacre, Fourth

Estate, London (2008), p 256-9

[So here are the natural

frequencies:

The much-quoted "60% reduction" in HIV transmission

after circumcision amounts to about 12

non-circumcised men per thousand infected per year,

and about 6 circumcised men per thousand per year in

those countries the trials were held in, where HIV

is rampant - far fewer where it is rarer, such as

the US.]

|

|

"... [P]hysicians have a moral

obligation to handle medical statistics in ways that

minimize unconscious bias. Otherwise, they cannot

help but inavertently manipulate both their patients

and one another ...

Sam Harris, "The Moral Landscape"

Random House 2010, p 143

|

The three trials compared

So far as we know, the results of the three trials are nowhere

else presented side by side. Their figures are not always

presented in comparable formats.

| Study |

Orange Farm, S A |

Kisumu, Kenya |

Rakai, Uganda |

Total |

| Author |

Auvert |

Bailey, Moses |

Gray, Quinn, Wawer |

|

| Publication |

PLOS Medicine |

The Lancet |

The Lancet |

|

| Date |

November 2005 |

February 24, 2007 |

February 24, 2007 |

|

| Number recruited |

3,274 |

2,784 |

4,996 |

11,054 |

|

| Method |

forceps-guided |

forceps-guided |

sleeve

procedure |

|

| |

Control (intact) |

Exper (cut) |

Control (intact) |

Exper (cut) |

Control (intact) |

Exper (cut) |

Control (intact) |

Exper (cut) |

|

| HIV- at start |

1,582 |

1,546 |

1,393 |

1,391 |

2,522 |

2,474 |

5,497 |

5,411 |

10,908 |

Total lost from study

(corrected

Mar

24, 2008) |

151 |

100 |

92 |

87 |

133 |

140 |

376 |

327 |

703 |

| Proportion lost from study |

9.5% |

6.5% |

9.6% |

10.1% |

5.3% |

5.7% |

6.8% |

6.0% |

6.4% |

| HIV+ |

45 |

20 |

47 |

22 |

45 |

22 |

137 |

64 |

201 |

| HIV+ (%) |

2.84% |

1.29% |

3.37% |

1.58% |

1.78% |

0.89% |

2.49% |

1.18% |

1.8% |

Absolute risk

reduction (%) |

|

1.55% |

|

1.79% |

|

0.90% |

|

1.31% |

|

| number “protected” |

|

25 |

|

25 |

|

23 |

|

73 |

|

“Protection” - raw

(Relative Risk Reduction) |

|

60% (95% CI: 32%-76%) |

|

53% (22-72) |

|

55% (95% CI 22-75; p=0·002) |

|

| - controlled |

|

61% (95% CI: 34%-77%) |

|

60% (32-77) |

|

60% (30-77; p=0·003) |

|

| Number to treat |

|

34 |

|

30 |

|

55 |

|

39 |

|

Method:

|

The foreceps-guided method, in which the foreskin is

pulled forward and cut, removes significantly less

mucosa than the sleeve procedure in which a strip of

tissue is taken from behind the glans (and a method

like the forceps-guided has been blamed for the high

rate of HIV infection in Lesotho, where most men are

circumcised). Yet the degree of HIV reduction is

substantially the same for the two methods -

suggesting circumcision is not what is causing the

difference.

|

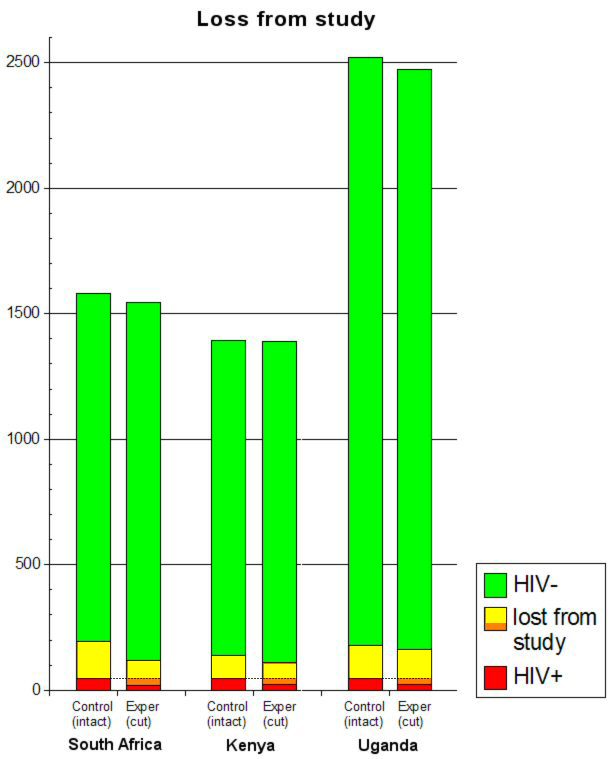

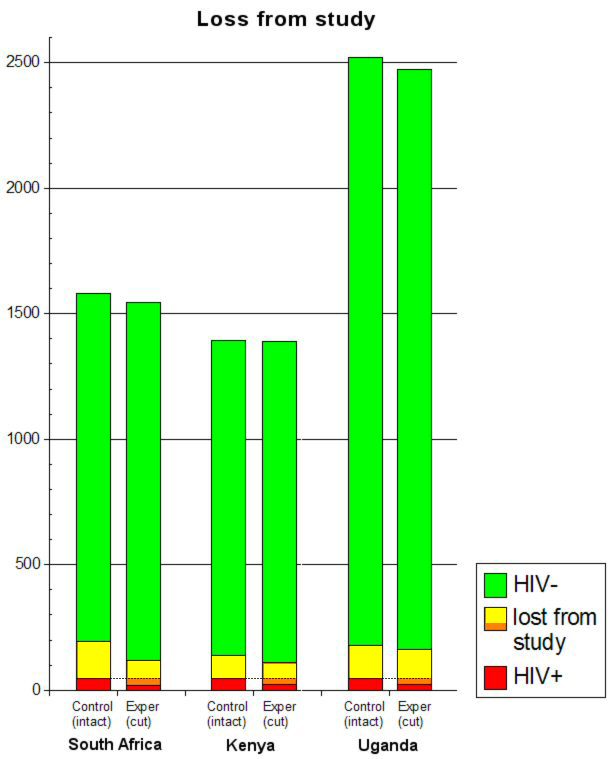

Loss from study

|

Ignore droputs

People who drop out of trials are statistically much

more likely to have done badly, and much more likely

to have had side-effects. They will only make your

drug look bad. So ignore them, make no attempt to

chase them up, do not include them in your analysis.

"Bad Science" by Ben Goldacre, Fourth

Estate, London (2008), p 209

|

|

All three trials had significant numbers "lost from

study", their HIV status unknown

(yellow+orange bars in the graphs below) - 100

circumcised subjects (6.5%) in South Africa, 87 (10%)

in Kenya and 140 (3.5%) in Uganda. (The figures are

presented confusingly in the studies because the men

did not all enter the trials together, but each trial

was stopped at a stroke.)

Those figures are high enough in themselves to cast

doubt on the validity of the results, but circumcised

men who found they had HIV would be disillusioned with

the trials and less likely to return. It would take

only 25, 25 and 23 such men respectively to completely

nullify the trials, and fewer to render the results

non-significant.

The orange part of each of the three right-hand bars

(below the dotted lines) represents the much-hyped

"60% protection" conferred by circumcision. If just

those men, whose HIV status is unknown, proved in fact

to be HIV+ (red), circumcision would certainly

have no protective effect whatever, but it would

not take all of them to reduce the effect below

statistical significance.

(One objection to this argument is that approximately

equal numbers of non-circumcised control-group members

dropped out. The answer to that is that a major and

very likely motivation for them to drop out would be

completely different and inapplicable to the

experimental group - to avoid getting circumcised.

Thus what needs explaining is why nearly equal numbers

of circumcised men dropped out, and an HIV+ diagnosis

could be an answer in a significant number of cases.)

|

Non-sexual transmission

|

In the South African trial, one third (23 of 69) of

the HIV infections occurred in men who reported no

unprotected sex during the period from their

last negative test to their first positive test. In

Uganda, 16 of 67 new infections occurred in men who

reported no sex partners (6 infections) or

100% condom use (10 infections). The trial in Kenya

did not report how sexual exposures related to HIV

incidence, except for seven men infected in the first

three months (sensitive tests did not find HIV in the

men's blood at the beginning of the trial). Five of

those seven, including three of four who had been

circumcised, reported no sexual exposures from

the beginning of the trial until their first

HIV-positive test.

|

Blood-borne transmission

|

The studies ignored exposure to HIV by blood.

In the two studies that reported information on

genital symptoms, 30-43% of infections with HIV

occurred during intervals when men reported genital

ulcers or other genital symptoms or problems. Because

genital symptoms were more common in uncircumcised

men, they may have been more likely to contract HIV

from skin-piercing procedures such as injections to

treat genital symptoms, but the studies did not

consider that possibility. None of the studies

reported on injections or on any other blood exposures

during follow-up. In the Kenyan trial, four men became

HIV-positive a month after circumcision, so the

circumcision itself might have infected them, but the

study did not mention that possibility.

|

Effect of cutting the studies short

|

'The best of five ... no ... seven ... no ...

nine!"

If the difference between your drug and placebo

becomes significant four and a half months into a six

month trial, stop the trial immediately and start

writing up the results: things might get less

impressive if you carry on.. Alternatively, if at six

months the results are 'nearly significant', extend

the trial by another three months.

"Bad Science" by Ben Goldacre, Fourth

Estate, London (2008), p 210

|

|

Randomized trails stopped early for benefit: a

systematic review.

Montori VM, Devereux PJ, Adhikari NK, et al.

JAMA 2005; 294:2203-09

Conclusion

Randomized clinical trials stopped early for benefit

are becoming increasingly common, particularly in top

medical journals. Adequate descriptions of the methods

used to inform the decision to truncate the trial are

often lacking. Trials stopped

early for benefit, particularly those with few

events, often report treatment effects that are

larger than typical of interventions that have been

definitively studied. These considerations

suggest that clinicians should view

results of RCTs stopped early for benefit with

skepticism.

|

|

Stopping Randomized Trials Early for Benefit and

Estimation of Treatment Effects

Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis

D. Bassler, M. Briel, V. M. Montori, M. Lane, P.

Glasziou, Qi Zhou, D. Heels-Ansdell, S. D. Walter, G.

H. Guyatt and the STOPIT-2 Study Group

JAMA. 2010;303(12):1180-1187

ALTHOUGH RANDOMIZED CONtrolled trials (RCTs)

generally provide credible evidence of treatment

effects, multiple problems may emerge when

investigators terminate a trial earlier than planned,

especially when the decision to terminate the trial is

based on the finding of an apparently beneficial

treatment effect. Bias may arise because large random

fluctuations of the estimated treatment effect can

occur, particularly early in the progress of a trial.

When investigators stop a trial based on an apparently

beneficial treatment effect, their results may

therefore provide misleading estimates of the benefit.

Statistical modeling suggests that RCTs stopped early

for benefit (truncated RCTs) will systematically

overestimate treatment effects, and empirical data

demonstrate that truncated RCTs

often show implausibly large treatment effects.

...

Context

Theory and simulation suggest that randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) stopped early for benefit

(truncated RCTs) systematically overestimate treatment

effects for the outcome that precipitated early

stopping.

Objective

To compare the treatment effect from truncated RCTs

with that from metaanalyses of RCTs addressing the

same question but not stopped early (nontruncated

RCTs) and to explore factors associated with

overestimates of effect.

Data Sources

Search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Current Contents, and

full-text journal content databases to identify

truncatedRCTs up to January2007; search ofMEDLINE,

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Database

of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects to identify

systematic reviews from which individual RCTs were

extracted up to January 2008.

Study Selection

Selected studies were RCTs reported as having stopped

early for benefit and matching nontruncated RCTs from

systematic reviews. Independent reviewers with medical

content expertise, working blinded to trial results,

judged the eligibility of the nontruncated RCTs based

on their similarity to the truncated RCTs.

Data Extraction

Reviewers with methodological expertise conducted data

extraction independently.

Results

The analysis included 91 truncated RCTs asking 63

different questions and 424 matching nontruncated

RCTs. The pooled ratio of relative risks in truncated

RCTs vs matching nontruncated RCTs was 0.71 (95%

confidence interval, 0.65-0.77). This difference was

independent of the presence of a statistical stopping

rule and the methodological quality of the studies as

assessed by allocation concealment and blinding. Large

differences in treatment effect size between truncated

and nontruncated RCTs (ratio of relative risks

<0.75) occurred with truncated RCTs having fewer

than

500 events. [The

three HIV-circumcision RCTs had a total of 196

events] In 39 of the 63 questions

(62%), the pooled effects of the nontruncated RCTs

failed to demonstrate significant benefit.

|

Comment

...On average, the ratio of RRs in the

truncated RCTs and matching nontruncated

RCTs was 0.71. This implies that, for

instance, if the RR from the nontruncated

RCTs was 0.8 (a 20% relative risk

reduction), the RR from the truncated RCTs

would be on average approximately 0.57 (a

43% relative risk reduction, more than

double the estimate of benefit).

Nontruncated RCTs with no evidence of

benefit—ie, with an RR of 1.0— would on

average be associated with a 29% relative

risk reduction in truncated RCTs addressing

the same question.

[This suggests

that the three HIV-circumcision RCTs

would have showed much less benefit -

none? - if they had not been truncated.

Circumcision advocates mention the

curtailing of the trials as an

indication of how beneficial

circumcision is, when the reverse may be

the case.]

|

Conclusions Truncated

RCTs were associated with greater effect sizes than

RCTs not stopped early. This difference was

independent of the presence of statistical stopping

rules and was greatest in smaller studies.

|

Our results have important implications for

systematic reviews and ethics. If reviewers

do not note truncation and do not consider

early stopping for benefit, meta-analyses

will report overestimates of effects.

...

data monitoring committees ...

have an ethical obligation to future

patients who need to know more than whether

data crossed a significance threshold; these

patients need precise and accurate data on

patient-important outcomes, of both risk and

benefits, to make treatment choices. Such

patients will often number in the tens or

hundreds of thousands and sometimes in the

millions. To the extent that substantial

overestimates of treatment effect are widely

disseminated, patients and clinicians will

be misled when trying to balance benefits,

harms, inconvenience, and cost of a possible

health care intervention. If

the true treatment effect is negligible or

absent—as our results suggest it sometimes

might be—acting on the results of a trial

stopped early will be even more

problematic. Thus, for trial

investigators, our results suggest the

desirability of stopping rules demanding

large numbers of events. For clinicians,

they suggest the

necessity of assuming the likelihood of

appreciable overestimates of effect in

trials stopped early.

|

|

A parallel case:

|

BBC

News

April 8, 2008

Halted drug trial safety concerns

The benefits of some cancer drugs may be exaggerated

as a rising number of trials are stopped early,

experts say.

Italian researchers analysed 25 trials, including

some for the breast cancer therapy Herceptin, that

were stopped early between 1997 and 2007.

The Mario Negri Institute team said data from many of

the recent cases had been used to get drug licences

before the long-term impacts were known.

But drug firms said finishing trials early saved

lives.

The Annals of Oncology report showed that of the 25

trials randomly chosen, 14 had been stopped in the

past three years.

And of these, 11 were used to support applications

for marketing authorisation from regulators.

Lead researcher Dr Giovanni Aplone said the increase

in early conclusions to trials suggested drug firms

were using good interim results to get their products

to market more quickly.

But he warned: "Data on

effectiveness and potential side-effects can be

missed by stopping a trial early."

He admitted there was no hard evidence of this, but

said there was an in-built bias

in the system because trials were often only stopped

early because the results were positive, when

this could just be a "random

high".

Positive results

Meanwhile, those that did not show such positive

results were given more time to prove their worth.

The team found that the

average study duration was 30 months - when the

long-term impact could only be judged over years.

The report also said some trials only enrolled less

than 40% of the total patients planned.

Researchers said regulators needed to take into

account the impact of stopping a trial early when

making decisions about licences.

And they added there needed to

be more use of independent monitoring committees

to verify trial data. Only the largest trials tend to

take this approach.

Professor Stuart Pocock, an expert in medical

statistics from the London School of Hygiene and

Tropical Medicine, agreed the issue was a

problem not just for cancer drugs but all kinds of

treatment.

He acknowledged trial organisers faced a dilemma when

results were positive because those patients involved

in the studies, but not receiving the therapies, could

lose out.

But he added: "We need proof beyond reasonable doubt

to stop a trial early."

...

|

|

All three of the Random Clinical Trials of

circumcision to prevent infection of men, were cut

short early, "because circumcision worked so well". The Ugandan trial of

transmission from HIV+ men to women was cut

short early because it was "futile".

If the African studies had not been stopped early and

long-term results had been obtained, the HIV infection

rate might very well have become statistically

insignificant between the circumcised and

non-circumcised groups. Look at the progression in the

number of cases of HIV in the Kisumu study:

Period since

Start of study |

Circumcised

(n=1391) |

Not circumcised

(n=1393) |

| 0- 1 month |

4 |

1 |

| 1- 3 months |

2 |

3 |

| 3- 6 months |

5 |

9 |

| 6-12 months |

3 |

18 |

| 12-18 months |

0 |

7 |

| 18-24 months |

8 |

9 |

The number of cases in each period for each group is

small, so their relative sizes are affected greatly by

random variation. It appears from the data that the

rate of infection is lower among the circumcised men

in the first 18 months following circumcision, but

that there's little difference beyond 18 months. If

the study had not been terminated early at 24 months,

it is quite likely that the number of HIV cases

between the groups would have become insignificant.

The decision to terminate the studies early prevented

any future comparison of the progression of HIV in the

circumcised and control groups and the very real

possible invalidation of the alleged "proof".

One of the researchers (Gray) has the nerve to

extrapolate the figures into the future from his

truncated study, claiming to show that the rate of

"protection" increases over time:

|

Title:

CROI:

Circumcision

could particularly benefit higher-risk

men

Author: Carter M | Cairns G

Corporate Author: AIDSMAP

Source: 4 Mar 2007

Abstract:

Clinical trials may have understated the

HIV prevention benefit of circumcision,

according to the lead investigator on a

recently reported study. The benefit

appears to grow over time and may be

highest in men with multiple partners, the

Fourteenth Conference on Retroviruses and

Opportunistic Infections heard this week

in Los Angeles. As already reported, two

trials of circumcision as an HIV

prevention measure for men in Rakai,

Uganda and Kisumu, Kenya were halted early

last December when it became apparent that

in both trials circumcision had

approximately halved the risk of acquiring

HIV. Ronald Gray, lead investigator of the

Rakai trial, gave more details to the

Fourteenth Conference on Retroviruses and

Opportunistic Infections in Los Angeles

last week. He said that the benefit of

circumcision was probably greater than the

preliminary efficacy of 51% would

indicate. This is both because the

benefit, for reasons as yet unclear,

appears to grow over time and because the

highest-risk men, namely those with

multiple partners and/or with genital

ulcer disease, appeared to particularly

benefit. Gray told the conference that the

protective effect of circumcision appeared

to increase over time. HIV incidence for

circumcised men was 1.19% a year from 0-6

months after circumcision [14

cases], 0.42% from 6- 12

months [5 cases]

and 0.40% from 12-24 months [3

cases]. This reduction over

time was statistically significant too

(p=0.0014). The corresponding incidence

rates in uncircumcised men for the same

time periods were 1.58% [19

cases], 1.19% [14

cases] and 1.19% [12

cases]. Gray said that

circumcision appeared to protect against

some, but not all, other sexually

transmitted infections.

|

One probability is that the incidence in the first

six months is higher because they got HIV from their

circumcisions! - if there is any non-random causal

relationship at all.

It is utterly innumerate to extrapolate anything from

such tiny numbers of cases, p-values or not. If he'd

done the same to the intact men, he'd find the

"protection" from being intact increased over time

too!

|

A

mathematical extrapolation of that study claims that mass

circumcision "could avert 2.0 (1.1-3.8) million new HIV

infections and 0.3 (0.1-0.5) million deaths over the next ten

years in sub-Saharan Africa. In the ten years after that, it

could avert a further 3.7 (1.9-7.5) million new HIV infections

and 2.7 (1.5-5.3) million deaths."

This has been widely broadcast around the world with new

headlines like "Circumcison could save millions - WHO" (Dominion

Post, Wellington New Zealand, July 12, 2006)) - even though the

new paper is nothing but a mathematical work up of the Auvert

study, which actually found a mere 29 (49-20) circumcised men

who did not contract HIV in 21 months - compared with 20

circumcised men who did contract HIV.

In other words, each of those 29 men has been extrapolated to

more than 125,000 infections and 93,000 deaths prevented - an

outrageous assumption from such a small number.

The paper's authors assume (without saying) that:

- Circumcision is cost-free and risk free

- All circumcisions are equivalent

- Circumcision has no effect on sexual behaviour

- A programme of mass circumcision will have no effect on

other AIDS-prevention programmes

- Men will volunteer for circumcision regardless of the

riskiness of their sexual behaviour.

All these assumptions are false.

This study has been quite invalidated

by the November 2007 announcement that the

number of HIV cases worldwide is much lower than was

previously estimated.

The study's authors are Brian G. Williams, James O.

Lloyd-Smith, Eleanor Gouws, Catherine Hankins, Wayne M. Getz,

John Hargrove, Isabelle de Zoysa, Christopher Dye and Bertran

Auvert. Auvert is the lead researcher of the first of the three

studies (Orange Farm, South Africa) making the claim that

circumcision protects against HIV. According to the paper, he

proposed the development of the model used and was one of those

who developed and applied the model.

Auvert himself did not (at first) advocate circumcision:

|

Medscape

Dr.

Wainberg: Are we ready as a world to make

recommendations in regard to more widespread

surgical procedures such as male circumcision?

Dr.

Auvert: The answer is no. For sure we have a

clear scientific answer about the association

between circumcision and HIV infection. For sure we

have demonstrated that in South Africa and this part

of the world we did see a population level reduction

of HIV infection in this trial, but we are not ready

to use this as a prevention method right now. The

situation in Africa is quite complex -- you've got a

lot of different cultural situations and it's not

possible.

|

|

The

Lancet 2006; 368:1236

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69513-5

Correspondence

Cautious optimism for new HIV/AIDS

prevention strategies

Edward

Mills a and Nandi Siegfried b

The

2006 International AIDS Conference, showcased in the

special (Lancet) Red issue, was filled with promises

for effective prevention strategies. Media attention

and plenary speeches suggested that effective

strategies, notably male circumcision and

pre-exposure prophylaxis (PREP), are imminent.1

Instead we advise cautious optimism.

The inferences drawn from

the only completed randomised controlled trial (RCT)

of circumcision could be weak

because the trial stopped early.2

In a systematic review of RCTs stopped early for

benefit,3 such RCTs were found to

overestimate treatment effects. When trials with

events fewer than the median number (n=66) were

compared with those with event numbers above the

median, the odds ratio for a magnitude of effect

greater than the median was 28 (95% CI 11-73). The

circumcision trial recorded 69 events, and is

therefore at risk of serious effect overestimation.

We

therefore advocate an impartial meta-analysis of

individual patients' data from this and other trials

underway before further feasibility studies are

done.

Although the rationale for PREP is

exciting, researchers have leapt from small

(n=6-18) and inconsistent non-randomised monkey

studies into multicentred trials.4 The

first PREP trial results were provided at the

conference,5 but had an insufficient

number of infections to provide any inferences

about effectiveness (two of 363 vs six of 368).

New

interventions are required to slow the HIV/AIDS

pandemic. Disappointments stemming from media hype

and misinterpretation of early trials can make

policy and recruitment of appropriate trial

populations difficult. If we are to alter the

epidemic's progress, we should be methodologically

rigorous, and cautiously optimistic about the

potential for new interventions.

We

declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

1.

Saletan W. When cutting isn't cruel. Washington Post

Aug 20 2006; B02.

2.

Siegfried N. Does male circumcision prevent HIV

infection?. PLoS Med 2005; 2: e393. CrossRef

3.

Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Adhikari NK, et al.

Randomized trials stopped early for benefit: a

systematic review. JAMA 2005; 294: 2203- 2209.

CrossRef

4.

Mills EJ, Singh S, Singh JA, Orbinski JJ, Warren M,

Upshur RE. Designing research in vulnerable

populations: lessons from HIV prevention trials that

stopped early. BMJ 2005; 331: 1403-1406. CrossRef

5.

Peterson L, Taylor D, Clarke EEK, et al. Findings

from a double- blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

trial of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for

prevention of HIV infection in women. XVI

International AIDS Conference; Toronto, Canada; Aug

17, 2006. Back to top

Affiliations

a.

Centre for International Health and Human Rights

Studies, 1255 Sheppard Avenue East, Toronto, Ontario

M2K 1E2, Canada

b.

Clinical Trial Service Unit, Department of Medicine,

University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

|

|

The Hawthorne Effect

The

Hawthorne

effect refers to the phenomenon that when people

are observed in a study, their behavior or performance

temporarily changes. Others have broadened the

definition to mean that people’s behavior and

performance change, following any new or increased

attention. The term gets its name from a factory

called the Hawthorne Works in Illinois, where a series

of experiments on factory workers were carried out

between 1924 and 1932. Most notably, production went up

when the lighting was increased, and it went up

when the lighting was decreased: it was the

attention the workers were getting when the

measurements were taken, not the lighting, that caused

the effect.

The Randomised Controlled Trials are subject to the

Hawthorne Effect because they were not double blind:

all the subjects knew which group they were in, and

what effect this was supposed to have. The Hawhtorne

Effect could not have directly affected the extent to

which they were infected with HIV, but it could have

affected their sexual behaviour, making the

circumcised men more aware of safer sexual practises

(having part cut off one's penis concentrates the mind

wonderfully), and perhaps more likely to implement

them. They reported no change in their sexual

behaviour, but self-reporting may not be accurate:

their reporting of homosexual behaviour, for example,

is so low it attracts the strong suspicion that they

were under-reporting it.

|

A comprehensive critique:

Male

Circumcision and HIV Prevention:

Is There Really Enough of the Right Kind of

Evidence?

Gary

W Dowsett, Murray Couch

"At Toronto, sociologists and anthropologists in

particular were sceptical of the narrow form of

''science'' being touted as the only form of evidence

needed. Activists and practitioners, e.g. people

living with HIV and AIDS, those working in the

non-governmental sector and prevention workers - those

who comprise the bulk of the ''AIDS community'' - were

concerned with a potential undercutting of their

hard-won shifts in sexual cultures, in many places,

toward safe sex practices." ...

"After all, these trials were not test tube

experiments but experiments conducted in clinical

settings. Such settings are profoundly social moments

with real human interactions and complex components,

even if RCT design in principle tries to circumvent

such inputs. For example, how

do we assess the fact of these trials not being

double-blinded: the men in each arm clearly knew

their circumcision status? That known difference

could have affected how the men responded

behaviourally, psychologically and sexually."

A literature search found a much greater proportion

of the studies of circumcision were of adverse

effects, ethics, ethnology, history, legislation and

jurisprudence, than (the proportion) of the studies of

appendectomy ("the surgical removal of a part of the

body seen as somewhat unimportant") or hysterectomy

("a more serious and controversial sexual and

reproductive health operation") .

From the conclusion:

"We believe we need to know much more about male

circumcision for HIV prevention before adopting it as

a population health measure. The WHO/UNAIDS Statement

is cautious in noting the existence of caveats and

gaps, but it argues that it is time to go ahead. We

would argue that there is still much work to do before

national authorities and the global HIV/AIDS community

can feel confident about proceeding."

Reproductive Health Matters

2007;15(29):33-44

|

Gary Dowsett was the only person the least

bit skeptical about the benefits of genital cutting who was

invited to the WHO/UNAIDS meeting at Montreux, Switzerland in

2007 where genital cutting was set as a mass intervention to

protect against HIV. As Intactivists suspected, the meeting was

gerrymandered by circumcision advocates Daniel Halperin, Robert

Bailey, Robert Gray and others to rubberstamp their

recommendation.

How the WHO was manipulated into

promoting genital cutting as

an HIV prevention

|

Global Public Health,

Hybrid forum or network?

The social and political construction of an

international ‘technical consultation’:

Male circumcision and HIV prevention

Alain Giami, Christophe Perrey, André Luiz de

Oliveira Mendonça & Kenneth Rochel de Camargo

Abstract

The technical consultation in Montreux, organised by

World Health Organization and UNAIDS in 2007,

recommended male circumcision as a method for

preventing HIV transmission. This consultation came

out of a long process of releasing reports and holding

international and regional conferences, a process

steered by an informal network. This network's

relations with other parties is analysed along with

its way of working and the exchanges during the

technical consultation that led up to the formal

adoption of a recommendation. Conducted in relation to

the concepts of a ‘hybrid forum’ and ‘network’, this

article shows that the decision was based on the

formation and consolidation of a network of persons.

They were active in all phases of this process,

ranging from studies of the recommendation's efficacy,

feasibility and acceptability to its adoption and

implementation. In this sense, this consultation

cannot be described as the constitution of a ‘hybrid

forum’, which is characterised by its openness to a

debate as well as a plurality of issues formulated by

the actors and of resources used by them. On the

contrary, little room was allowed for contradictory

discussions, as if the decision had already been made

before the Montreux consultation.

Excerpts:

There was but one avowed opponent in this group: Gary

Dowsett, an Australian sociologist who had extensive

experience in social science research on AIDS and had

served as consultant for WHO and other international

organisations. As one of a group of self-identified

gay researchers, his activities in this field reached

back to the mid-1980s. Nonetheless, the possibility

for him to present his critique was limited by both

the agenda and the perceived hostility towards him

during discussions by, in particular, a major US

epidemiologist, one of the recommendation’s principal

advocates. During our interview, Dowsett cited this

person’s name, which we have replaced with the pronoun

HE in the transcripts:

I’m standing in the hotel, with a glass of

champagne and HE … comes charging over to me,

immediately … and just started to attack me,

immediately, and … ‘How wrong I was! Why I was doing

this? I got the argument wrong – Did I not understand

how important all this was’ … and HE attacked me …

every time I spoke in the meeting at Montreux. Every

time!

...

According to some interviewees, the time devoted to

the presentations did not allow for a genuine, open

debate, in particular about how to extrapolate from

the findings in the narrow context of the RCTs to the

general population. This question was thought to be

settled, given the results from previous observational

and epidemiological studies. There was no mention of

the contradictory findings that had been published,

nor of a scientific controversy. According to Dowsett

during our interview, Hankins’ speech on the second

day barely mentioned the recommendation’s social and

cultural consequences:

We were concerned about the cultural consequences

of circumcision in terms of shifting ideas of

sexuality, sexual cultures and masculinity; and any

evaluation of circumcision being rolled out needed to

include much broader social and cultural markers than

simply medical and behavioural markers of the

implementation. That was part of the recommendations

for the research agenda, from the social science

meeting in Durban. That was simply reported in

Montreux, and nothing was either endorsed or done

about it. It was just presented as background

information.

|

Followup in South Africa: Correlation is not causation

|

Circumcision

October 3, 2013

Aidsmap

Cross-sectional study suggests circumcision is having

a big impact on HIV rates among men in Orange Farm,

South Africa

by Michael Carter

Research conducted in South Africa suggests that the

roll-out of circumcision is reducing the prevalence and

incidence of HIV among men. Published in PLOS

Medicine, the study also showed circumcision does

not lead to the adoption of riskier sexual behaviour

that could potentially cancel its benefits.

The French researchers who conducted the study [the

very

same people who made the original claim]

believe its findings support the accelerated roll-out of

circumcision programmes for men living in settings with

high HIV prevalence.

The results of three randomised controlled trials

published between 2005 and 2007 showed that circumcision

reduced men’s risk of infection with HIV by between 50

and 60%. As a result, since 2007 both UNAIDS and WHO

have recommended that voluntary medical male

circumcision (VMMC) programmes should be incorporated

into prevention initiatives in settings with a high HIV

prevalence.

However, little is known about the impact of

circumcision roll-out programmes on the spread of HIV

among men. [And isn't that a

scandal in itself?]

French investigators from the Bophelo Pele project

designed a cross-sectional study involving men in the

Orange Farm township in South Africa. The first

randomised controlled trial to test the effectiveness of

VMMC on HIV acquisition was conducted in the township

between 2002 and 2005.

Roll-out of VMMC started in Orange Farm in 2008 and

between 2007 and 2008 the French investigators recruited

1998 men between the ages of 15 and 49 years to a

baseline survey. The men were tested for HIV, their

circumcision status was determined and demographic data

were collected. The men were also asked about their

sexual risk behaviour, including condom use and number

of non-spousal partners.

A follow-up survey was conducted in 2010 and 2011 and

involved 3388 men. [So at

least 1/3 of the men were not in the first part of

the "follow-up" study". Strange.]

The investigators calculated the prevalence of

circumcision, compared HIV prevalence rates and sexual

risk behaviour between circumcised and uncircumcised men

and calculated the impact of circumcision roll-out on

HIV incidence.

Circumcision prevalence increased from 17% in the

baseline survey to 53% in the 2010-2011 survey.

“This study has shown that the roll-out of free VMMC

can lead to a substantial uptake in just a few years,”

comment the authors.

There were no significant differences in the [reported]

sexual behaviour of circumcised and uncircumcised men.

The proportion of circumcised and uncircumcised men

reporting consistent condom use in the previous twelve

months was 44 vs 45%. The proportion reporting two or

more non-spousal partners was 50 vs 44%.

The HIV prevalence rate among uncircumcised men was 19%

compared to 7% among circumcised men with an overall

prevalence rate of 12%. [But

we know that in 10 out of 18 other countries for

which USAID has figures, the ratio is the other way.

This could be unconnected to circumcision.]

The investigators calculated that it would have been

15%, almost a fifth higher, if the circumcision

programme had not been rolled out.

[Assuming what they want to prove, that genital

cutting is efficatious against HIV.]

Moreover, the authors also calculated that the roll-out

of VMMC reduced the incidence of new HIV infections by

between 57 and 61%.

“The roll-out of VMMC in this community was associated

with a reduction in the prevalence and incidence of HIV

among circumcised men in comparison with uncircumcised

men, and we estimate that without this project, HIV

prevalence averaged on all adult men would have been

significantly higher,” write the authors.

They acknowledge that their study has limitations,

chief among these its cross-sectional design. As

the study was not randomised, it could not prove a

causal relationship between circumcision status and

the risk of HIV infection.

Nevertheless, the authors believe their research shows

the value of circumcision and conclude: “the main

implication of this study is that the current roll-out

of adult VMMC…should be accelerated.” [And

Carthage

must be destroyed.]

|

Followup in Uganda: Is there even correlation?

|

Aidsmap

February 27, 2015

Circumcision is reducing HIV incidence in Uganda,

Rakai community study shows

by Keith Alcorn

The growing uptake of medical male circumcision by men

in the Rakai district of Uganda is leading to a

substantial reduction in HIV incidence among men in one

of the districts of the country worst affected by HIV,

Xiangrong Kong of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of

Public Health told the Conference

on

Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2015)

in Seattle, USA, on Thursday.

Three large clinical trials in sub-Saharan Africa,

including one conducted in the Rakai district [by

the authors of this follow-up study],

have shown that medical male circumcision reduces the

risk of acquiring HIV by between 50% and 60%. These

findings have led to the scale up of services offering

medical circumcision to men, especially to adolescents

and young men.

However, until now, the only evidence of an impact of

medical male circumcision on HIV incidence in the

communities where it is offered has come from a

cross-sectional study in the Orange Farm community in

South Africa, where another of the clinical trials

showing efficacy took place. That

study

showed that the roll out of circumcision had reduced

HIV incidence by between 57% and 61%.

The study conducted in Rakai set out to assess the

impact of scaling up circumcision in Rakai district

since 2007, through analysis of annual cross-sectional

surveys of adults aged 15-49 carried out by the Rakai

Community Cohort Study. The analysis excluded Muslim men

who would have been circumcised in any case [did

they have an embarrassingly high HIV rate?],

and sought to assess the impact of circumcision as an

HIV prevention intervention. The analysis also assessed

and controlled for the level of antiretroviral coverage

over time in women, since increased antiretroviral

coverage would be expected to reduce HIV transmission to

men, regardless of the level of circumcision.

The study found that circumcision coverage in

non-Muslim men increased from 9% during the Rakai

circumcision study to 26% by 2011, four years after the

trial concluded. Every 10% increase in circumcision

coverage was associated with a 12% reduction in HIV

incidence (0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.80-0.96). [Was this only among the

circumcised men, or also among the intact? In other

words, did the circumcision campaign just raise

public awareness of HIV prevention, and promote

safer practice overall?]

However, there was no evidence of a reduction of

incidence in women as a consequence of the reduction in

HIV prevalence in men due to circumcision. [A

study by these same authors started to find an increase

in the incidence in women, but they ignore this

possibility.] Dr Xiangrong Kong said that

previous modelling studies suggested it may take up to a

decade for medical male circumcision to have an impact

on HIV incidence in women. [Why

so long?]

Preliminary data for 2013-14 show that the proportion

of non-Muslim men who have undergone medical

circumcision in the Rakai Community Cohort has increased

to 49%.

|

A damning critique of the ethics of

these experiments

|

Developing

World Bioethics, Wiley Online Library, 09

September 2020 https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12285

A new Tuskegee? Unethical human

experimentation and Western neocolonialism in the

mass circumcision of African men

Max Fish, Arianne Shahvisi, Tatenda Gwaambuka,

Godfrey B. Tangwa, Daniel Ncayiyana, Brian D. Earp

Abstract

Campaigns to circumcise millions of boys and men to

reduce HIV transmission are being conducted throughout

eastern and southern Africa, recommended by the World

Health Organization and implemented by the United

States government and Western NGOs. In the United

States, proposals to mass?circumcise African and

African American men are longstanding, and have

historically relied on racist beliefs and stereotypes.

The present campaigns were started in haste, without

adequate contextual research, and the manner in which

they have been carried out implies troubling

assumptions about culture, health, and sexuality in

Africa, as well as a failure to properly consider the

economic determinants of HIV prevalence. This critical

appraisal examines the history and politics of these

circumcision campaigns while highlighting the

relevance of race and colonialism. It argues that the

“circumcision solution” to African HIV epidemics has

more to do with cultural imperialism than with sound

health policy, and concludes that African communities

need a means of robust representation within the

regime.

|

|

|